For a couple of days, we did nothing but cough and rest. But as we recovered, we ventured out in bursts to walk around Wakkanai. The place feels like a frontier town, and like many frontier towns, is full of interesting stories.

The city has also had a long history of trade, conflict and collaboration with the original Ainu inhabitants and with the Soviet Union and Russia. And it has long been a major fishing port of economic and political importance.

Ainu people, among the original inhabitants of Hokkaido, have lived here for hundreds of years. At the end of the 1600s, Japanese established a settlement to facilitate trade between the two peoples. At this time, there were many clashes between the Ainu and the colonisers as more Japanese moved to Hokkaido, which at the time they called Ezo. In 1869, the whole island was incorporated into Japan, and the Ainu dispossessed of their land and culture, and forced to assimilate. (This is a familiar story to anyone who lives in a country that has been colonised.) Hokkaido did not become a formal prefecture of Japan until 1947.

The geography and climate of Siberia and the Sea of Japan and a semi-permanent low around the Aleutian Islands mean that the weather can be pretty wild here. A great deal of infrastructure has been built to make the port safe. Among the infrastructure that is strictly functional and mostly uninspiring, the Breakwater Dome stands out. The underneath is open. Walking its length takes you beneath 70 arched ribs in a beautiful curve, each supported by a column in a Roman style. It has presence, being 416 metres long and 13.8 metres high, giving a fitting sense of strength to resist winter storms and drift ice. I love that the designer, engineer Minoru Tsuchiya, employed a temple carpenter to create the formwork to realise his vision. Construction of the breakwater finished in 1936, and it was partially rebuilt in the late 1970s to counteract the corrosion.

Large as it is, from the top of the hill behind the city, it becomes almost indistinguishable from the rest of the port infrastructure and you get an idea of the importance of the port to the city’s economy.

The role of fishing — and the politics of international fishing — in the economy is illustrated in text and photos in the Seto house in town.

Wakkanai local Tsunezo Seto became wealthy both from trawl fishing for herring that was ground up to fertilise southern cotton crops, and from numerous other sea creatures, with eel, flounder, mackerel, octopus, stingray and king crab among his fishing interests. As a display of his power and wealth, in 1952 Seto built an elegant house in the modern Japanese style with some Western elements. The house, now owned by the state and beautifully restored, contains a large room for hosting banquets (aimed at cementing his considerable influence?) and a special room for tea ceremony, both of which look over an elegant and calming traditional garden.

But the glory days were coming to an end. A brochure at the house noted that the Sea of Japan had been know as a herring fishing ground since at least the early 1600s, but that 1953 was the last hear herring came to spawn.

The plunder of other species continued for awhile, with the record catch (numbers and value) in 1976. Photos in the house show Wakkanai harbour crowded with fishing vessels moored to each other and filling the water from one side of the port to the other. Numerous trucks plied the pier between fishing vessels and markets, their open trays full of fish. Now, with international fisheries within 200 nautical miles of coasts being managed, only a few fishing vessels are licensed to operate out of Wakkanai, and the once-crowded port seems too large. Japan’s love affair with seafood is unsated. Even the smallest convenience store in the smallest villages offer a selection of prepared, frozen and fresh seafood, and it is on almost every cafe and restaurant menu we’ve seen near the coast.

On top of the hill above town are two monuments that introduce more of Wakkanai’s frontier history.

Overlooking the Sea of Japan is the Hyosetsu Gate, called in English the Gate of Ice and Snow. It is a monument to the resilience of 420,000 Japanese who, at the time World War 2 ended, lived on the island then called Karafuto, north of Hokkaido. Five days after the end of World War 2, when Japan was reeling from its defeat and the two atomic bombs that had been dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Soviet Union invaded Karafuto. Those Japanese who didn’t die in the fighting fled, arriving at the port of Wakkanai to begin to rebuild their lives. The monument is a testament to their resilience in this harsh climate. It expresses grief and appeals for mercy and peace. The island, now known as Sakhalin, is still Russian territory. On a clear day, it can be seen on the horizon behind the monument.

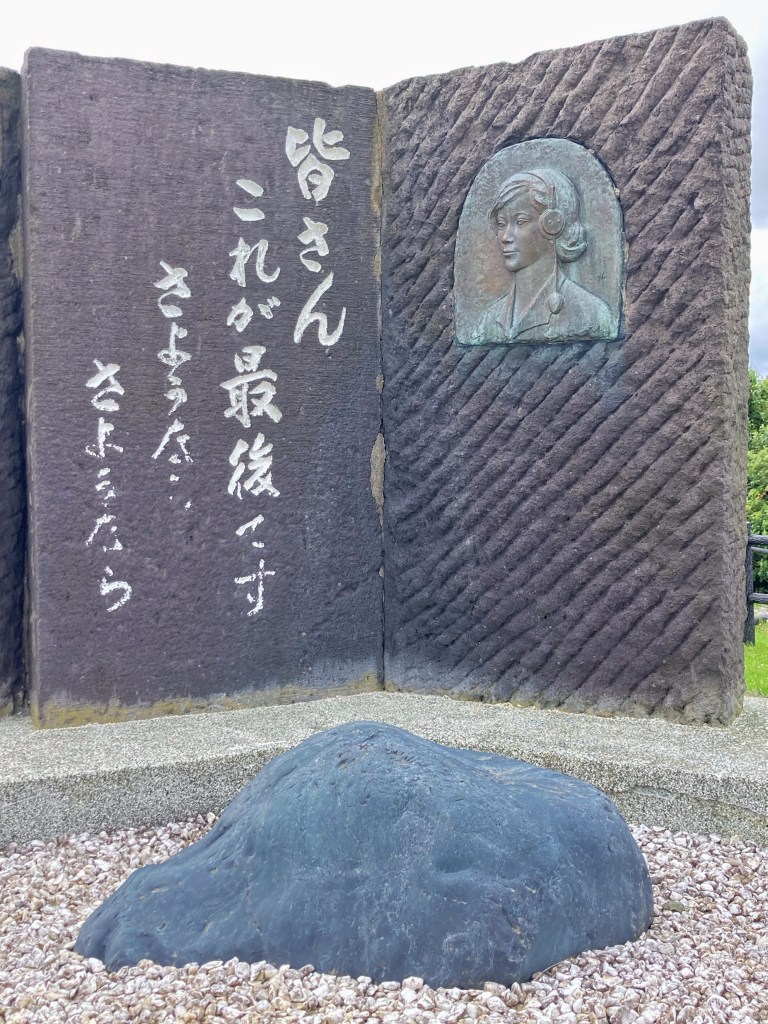

Next to the gate stands a humble stone memorial to 9 women who gave their lives during the same conflict. The women were switchboard operators who kept open lines of communication among the Japanese fighters in the town of Maoka (now Kholmsk) while fighting raged around them. When the town fell, the women killed themselves by swallowing potassium cyanide rather than become prisoners of war.

After four day’s rest in Wakkanai, we’d recovered enough to be sick of our sick selves and were keen to continue, despite still having coughs. We saddled up and headed to another north point: Cape Soya, the northernmost point of Japan.

The gusty headwind was so feral that it yawed randomly through all compass points, in the space of 30 seconds, blasting in our faces and slowing us to 8 km/h, before veering behind to push, and then slamming us sideways. Gusts reached 65 km/h (according to the weather app). It was only a 35-km day, but it was effortful riding, not just because of the strength of the wind but also was because we had to stay alert for any tiny changes in the wind to brace for the next shunt.

The day was sunny, though, and the ocean a deep blue, almost black, and covered with white horses. Eagles and gulls flew above us, looking only partly in control in the wind. We passed a few scattered settlements and tiny fishing ports created from concrete walls and groins along a coast that offers few natural harbours. Life looks tough along this section of coast. It felt as end-of-the-world as Rishiri and Rebun.

At Cape Soya, Japanese waited in a line to take their turn having their photo taken on the cape marker. We were in search of accommodation.

There was no camping, no hotel accommodation available, and no place protected enough from the wind to camp wild there. We back-tracked some kilometres (great tailwind!) to a tiny fishing port that also sported a children’s playground and toilets (which also meant a source of potable water). In the lee of an aquaculture building, we found a little protection from the wild wind and set up there for the night.

The next day would see us turn south-east down the coast on the Sea of Okhotsk.

Leave a comment