Eniwa lies 26 km south of Hokkaido’s capital, Sapporo, on the plain of the Ishikari River. Within two minutes of leaving the campsite, we had left behind arterial roads loud with peak-hour traffic and were on quiet farm roads on our way to the northernmost city of Japan, 375 km away.

Across the Ishikari valley, roads criss-crossed each other in neat grids, and within them, squares of neat fields furnished rice, wheat or barley, rice, potatoes and other vegetables, flowers, and rice. A network of irrigation channels meant water could be spread across some fields while others were kept dry. The floodplain is flat and wide here, as the Ishikari nears its mouth.

The heatwave of the past week continued, and by 10 am it was again 30 °C, with the humidity more than 90%. The air throbbed with heat and too much sunlight, and was echoed by choruses of cicadas that continued for kilometres. We soon came to the river itself, and veered onto a paved track that ran along the top of the river’s levee bank. Farm plots came right up to the edge of one side of the levee; on the river side, a wide margin of land had been left, looking as though the river was being allowed room to expand in floods before it reached the levee. This side was dense with stands of small trees and shrubs infilled by thick grasses studded with wildflowers.

We called it quits on riding for the day at about 1 pm so as to avoid the pummelling heat of early afternoon. This was part of our strategy for avoiding sunstroke and heat stress, to start early and finish early, even though it meant riding short days. We fell into this pattern easily over the next few days — the sun is up before 4.30 am anyway — stopping mid-morning to cool off in tree shade or in the air-conditioning of a konbini (convenience store), the source of most breakfasts and lunches and ingredients for dinner when towns are too small to have a supermarket. Konbini are also a reliable supplier of delicious Hokkaido ice-cream.

For most of the ride to Wakkanai, we had a tailwind. This did great things to our average speed, but it also meant we seldom got any cooling effect from breezes blowing in our faces.

We scooted along smartly over a few small hills, following the Ishikari with its many oxbows lying in blue curves among the vivid greens of wild vegetation and public parks in villages. Each crop has its own colour of green or gold (depending on ripeness) and these made an attractive patchwork pattern across the plain. Interspersed among the fields were barns with the wood left raw and gone grey or painted in bright colours. Turquoise and teal seem to be favoured in these parts. It was pretty riding.

We had our first night of wild camping at Shintotsukawa, after we learned that the campground had been converted to glamping and cabins. We scouted around the sports fields and found a nook out of sight where we would be able to erect the tent in the evening once day-time users had left. In the meantime, we made use of the onsen, the free (though poor) wifi, picnic tables and tap water.

The Ishikari bent north-east towards Asahikawa and the Daisetsuzan National Park, and we turned north-west towards Rumoi, on the Sea of Japan coast. The exhausting heat continued, and we stopped at a village when we saw a sink with a tap in a carpark. We bowed our heads like supplicants and let the cool water run over us.

We left the farming land behind as we started crossing lines of low hills that form the southern catchment of the Rumoi River. We were riding on route 233. We’d not been looking forward to it, especially after the days on farm roads. But it had less traffic than we had anticipated (probably because most of it used the adjacent E62 expressway) and most motorists gave us plenty of room.

With the continuing heatwave and after 10 consecutive nights in the tent, we’d decided to book into a hotel for a bed indoors and a rest day, and set about finding that in Rumoi. Most accommodation providers in Hokkaido require you to book by phone, impossible for us because of our lack of Japanese. So, we have to doorknock. Rumoi was full. There was not even a manger in a barn to be found. After 2 hours, and about to give up and camp, we finally came across a place on the edge of town. It turned out to be a ryokan, a traditional Japanese inn with tatami-matted floors and futons to sleep on. What an unexpected treat.

We were the only westerners there — in fact, we’ve seen hardly any westerners on our trip — and the staff seemed to enjoy rising to the challenge of educating us about how to behave in a ryokan. We were lent yukata (cotton robes) that you are welcome to lounge around in throughout the hotel and onsen. We lounged and bathed. Staff came to set up the low table in our room for our kaiseki dinner. This traditional multi-dish meal often features local specialties and is generally served in one’s room. We were on the coast, and our meal had mackerel, salmon, roe, sea urchin, a white-fleshed fish, prawn and kelp presented in 10 dishes. When you’ve finished, staff clear away the meal trays, move the table to the edge of the room, and get out our futons and make up our beds.

Breakfast was served in a communal dining room. It was quite acceptable to swan downstairs to breakfast in the yukata. Staff put away the futons for the day, and set the table back in the centre of the room. This ryokan was shabby, with threadbare, stained carpets and chipped paint. But the service was immaculate and the food faultless in presentation, flavour and texture.

After our taste of high living, we were back to the familiar grit, sweat and sunscreen of pedalling. We rode up the coast, through Obira and Tomamae, Harboro and Enbetsu to Teshio, the wind behind us pushing us along and enjoying a blessed 5 degree drop in temperature to 27 °C. The humidity stayed doggedly in the 90s.

On most days, we stopped for a cold drink at a michi-no-eki (roadside rest area that usually also showcases local produce). Along this stretch of coast, as well as produce there was a representative ‘herring house’ that had been moved from Rumoi and renovated as a tourist attraction.

Herring houses are a famous part of Hokkaido’s cultural history. This one was built in the early 20th century by Densaku Hanada, something of a herring fishing magnate. It’s beautifully constructed with elegant lines. The Hanada family lived in the house alongside about 200 fishermen who worked for them, plus ancillary staff such as boat builders and blacksmiths. The herring were turned into fertiliser to feed the cotton industry in the south, something that seems shocking and wanton to me living in an age of crashing fish numbers.

The coastal scenery was lovely, and a little wild looking with it’s wind-whipped seas, vegetation flourishing madly to make the most of the short summer, dark volcanic sands, jumbles of black rocks jutting out of the sea, and other-worldy wind turbines. But the whole 120 km of coastline we rode from Rumoi to Teshio was also a rubbish tip. It was distressing to see that there wasn’t a stretch of beach free of litter evidently washed off fishing vessels and into the sea from rivers. Millions of bits of plastic in various stages of falling apart the whole length of the coast.

Most campsites in Japan don’t provide showers, probably because there is usually an onsen nearby. It was the same in Teshio, where Claire enjoyed the bath more than usual because a local, Masako, stopped in the same pool to chat. Masako learned English on independent travel in the UK and from an English-speaking partner who, she said, had recently kicked her out of their Sapporo flat. Now she was making a new life in the small town of Teshio, where she had the friendship of other practising Christians and enjoyed conversing with the few English-speaking foreigners who pass through. It was only the second time I’d been able to talk to anyone at an onsen, so it made the whole experience of companionable public bathing seem more complete. Masako was a gracious self-appointed host.

A weather change came through, bearing rain that would come and go for a week. After the first early-morning downpour exhausted itself, we made a break for it. We made it to Horonobe, 22 km north-east, before the heavens unleashed the next downpour. As we went in search of the town’s public bath, which is in an old people’s home, we passed a smart little museum. The museum attendant beckoned us in to shelter. The museum turned out to be in honour of a local, a famous calligrapher named Shinzo Kaneda. It houses 1,200 of his calligraphic works, of which maybe 80 are on display, as well as hundreds of brushes and ink pads, and scores of tea pots and tea cups. It was a serene space, and the attendant welcoming, one of those delights of travel that stay with you because you weren’t expecting them and they delight you.

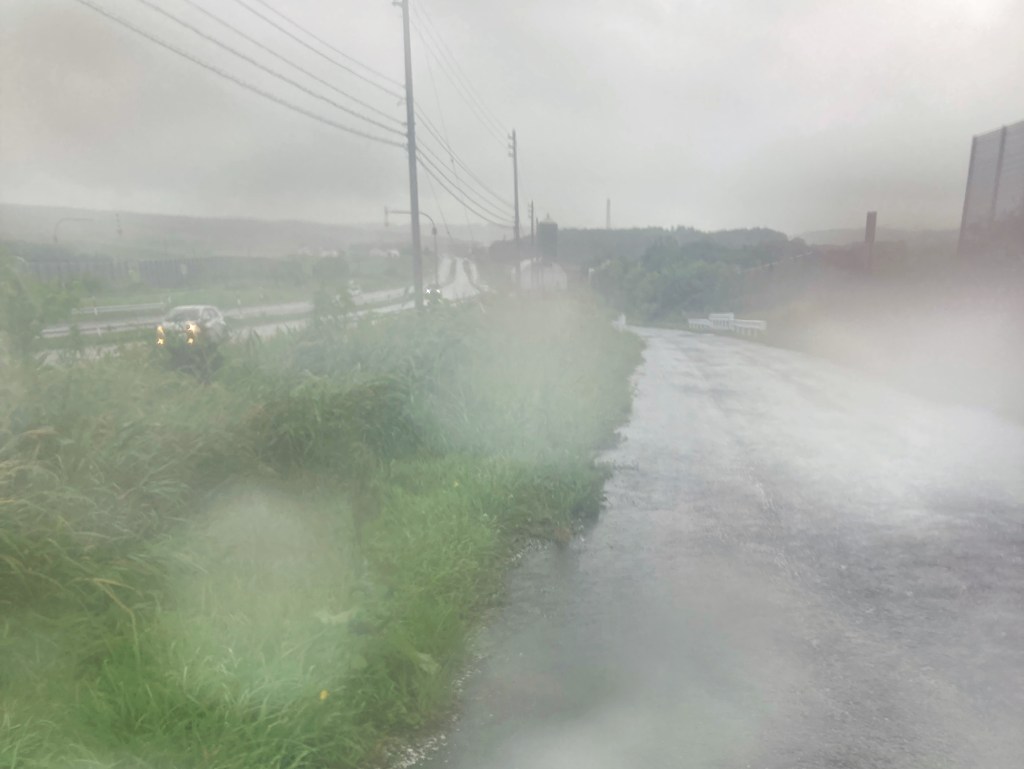

The next morning, under leaden skies and swirling winds, we set off on the last leg to Wakkanai, weather reports and signs above the road warning of flooding rivers, landslides, lightning and heavy rain. Every river and stream we crossed was surging with mud-saturated water. The first downpour of the day arrived as we pulled into the Kaigen parking shelter. What a blessing this ugly concrete bunker was! As well as providing under-cover parking for motorists, it came with drinks dispensers, squeaky-clean toilets with built-in heated seats and bidets, and a poster advertising vehicle support for minor repairs for cyclists riding by.

It was also the starting point of a bike path runs alongside the road for 15 km. Having a breather from highway riding in this weather was another blessing, even though motorists were considerate and gave us space when they could. We rode through a long downpour that eased as we came into Wakkanai, looking like half-drowned creatures fished out of the sea. It was midday, and we couldn’t get into the hostel we’d booked until 3 pm, so we huddled in a cafe in the Wakkanai train station and downed cheesecake and hot chocolate. By 4, we were tucked up freshly showered, warm and dry in Guesthouse Moshiripa, in the northernmost city of Japan.

Leave a reply to Kassie Heath Cancel reply